Shouldering Fabrication

Maryland C-Fab Specializes in a Wide Range of Upper-Extremity Prosthetics

Pinnacle Prosthetic Labs, based in Damascus, Maryland, specializes in central fabrication of upper-extremity prostheses. Its vice president for sales, Bruce Thomas, CO F, also is the owner of Pinnacle Orthopedic Services in nearby Germantown, an O&P distributor and services provider since 2010.

Thomas and his wife, Jacqueline, founded Pinnacle Prosthetic Labs to provide upper-extremity devices for local hospital facilities. The company’s patient population primarily consists of military personnel who have served in the most recent conflicts in the Middle East, although Thomas plans to grow within the region. “There are not a lot of labs local to the Maryland, Virginia, and [Washington] D.C. area,” he says, “and we’d like to expand in that market.” Pinnacle does not use computer-aided design and manufacturing at this point, although Thomas hopes to add it eventually.

The company is owned by Jacqueline Thomas, who is responsible for all operational functions at both Pinnacle Orthopedics and Pinnacle Prosthetic Labs. The c-fab employs Jack Stephens, CTPO, as a full-time technician, and fills in with part-time techs as needed.

For Bruce Thomas, staffing has been a running challenge for the growing company as it seeks to balance new business with the appropriate number of employees.

Both Thomas and Stephens stress that central fabrication of upper-extremity prostheses makes sense for most O&P facilities because shoulder, arm, and hand prostheses are relatively uncommon. “Most O&P offices will see one or two upperextremity cases a year,” says Thomas. “That’s all we do, and we have a combined track record of 23 years in the industry, so we have the experience and expertise to make it cost-effective.”

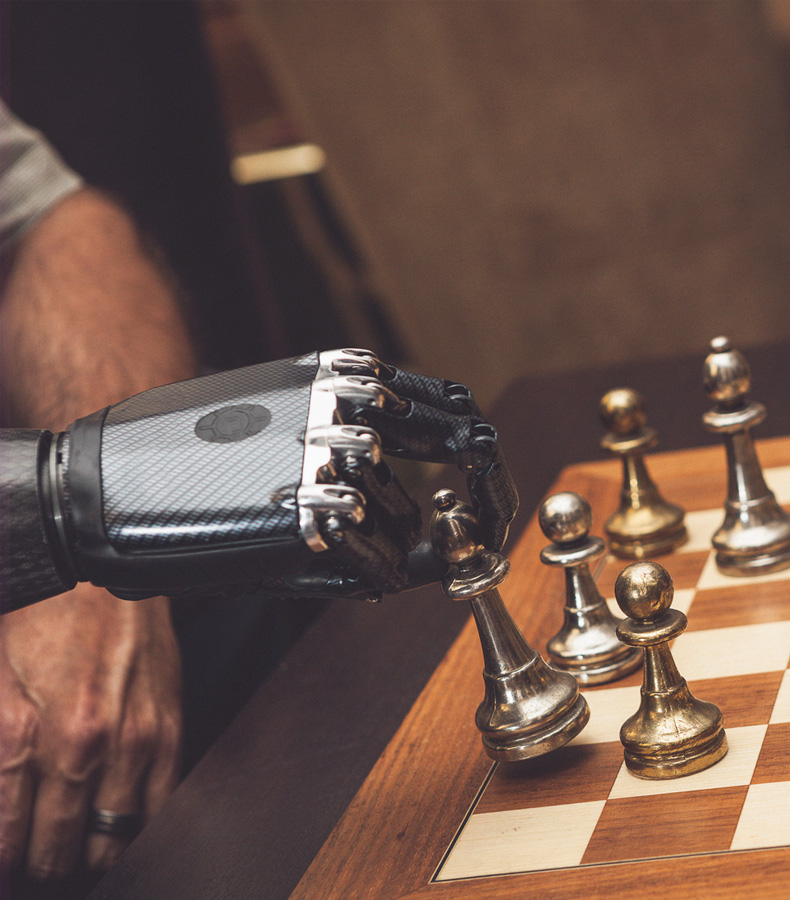

Stephens has fabricated the full gamut of upper-extremity prostheses, from body-powered devices with cables to advanced myoelectric prostheses, as well as partial-hand devices. He makes hybrid arm prostheses as well, which combine a body-powered elbow with a myoelectric hand.

“Users can shrug their shoulders to lift the elbow and manually lock and unlock the position,” he explains. A hybrid device is lighter than an electrically powered arm, which would require another motor and additional batteries.

Stephens also fabricates prosthetic devices that use pattern recognition. “I’m making a COAPT arm right now for a patient,” he says. “To use the arm, he had to start with surgery to relocate nerves to the surface of his triceps and bicep muscles.”

In training sessions for patternrecognition devices, patients try to flex their “phantom” elbow, which triggers the relocated nerves to send signals to eight electrodes placed on the muscles. Clinicians assign the pattern of those signals to the elbowflexing motion, and ultimately users can flex the prosthetic elbow just by thinking about it.

“There is a lot of research going in this field, and we get to see it at local hospital facilities,” says Stephens. “We are currently working with the Alfred Mann Foundation on a research pattern-recognition arm.” Stephens often creates prostheses that enable an amputee to perform specific tasks. “I’ve made arms for driving, riding a bike, golfing, playing baseball, bow hunting, and playing a guitar,” he says. “Some of the soldiers like to shoot, and they need to be able to hold the gun and rack the slide on a pistol.”

So far, Pinnacle Prosthetic Labs has focused its marketing efforts on industry expositions such as the AOPA National Assembly, but it is in the process of launching a website and expanding its marketing efforts throughout the metropolitan Washington, D.C., region. Ultimately, says Thomas, “We want to provide quality service in a timely way.” CP

Deborah Conn is a contributing writer to O&P Almanac. Reach her at deborahconn@verizon.net.

Source: O&P Almanac, December 2015